Barcelona 24.12.2020 - 45 years of the Can Serra objectors, the beginning of the largest civil disobedience movement in Europe

Pol Pareja, Barcelona, December 24, 2020

A group of young men stood before military service on Christmas night in 1975 and with them began a fight that would involve tens of thousands of people over 30 years.

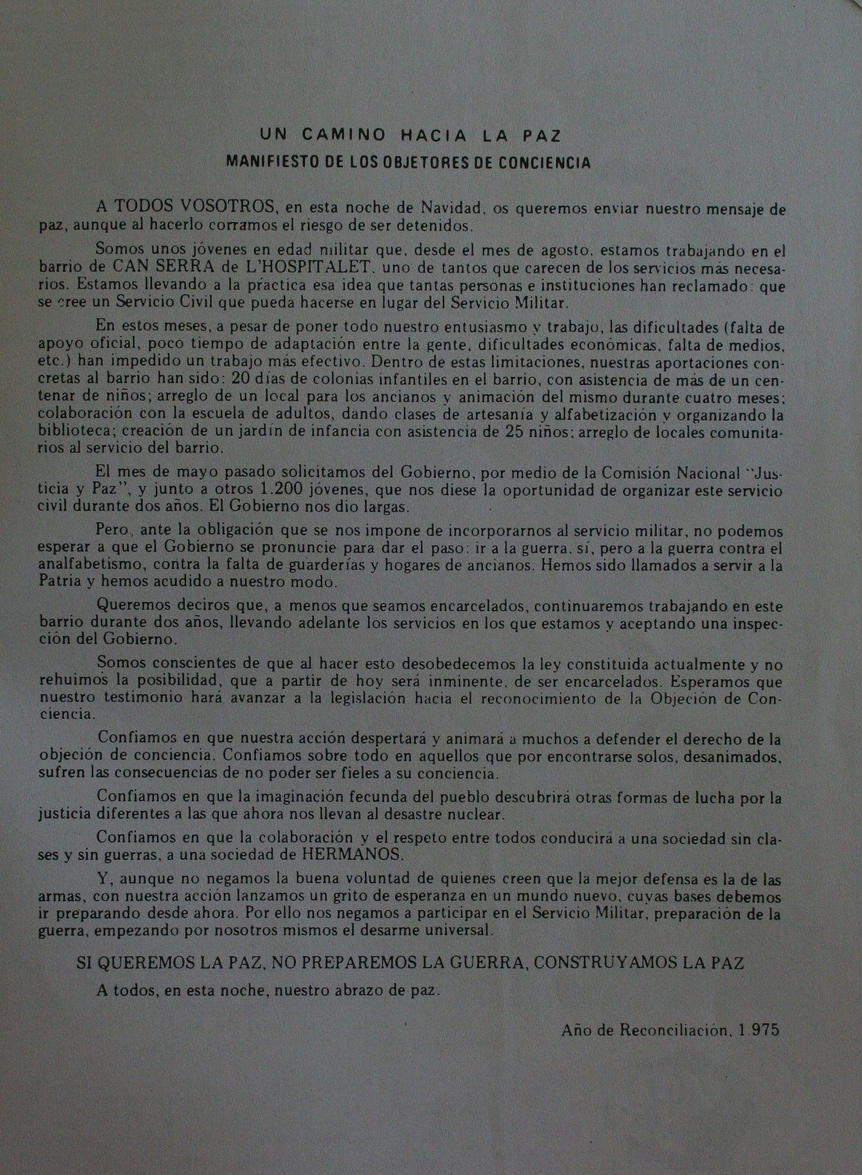

"To all of you, on this Christmas night, we want to send our message of peace even though in doing so we run the risk of being arrested."

The message was signed by a group of young people and was read in several Catalan churches during the Mass of the Rooster on Christmas night 1975. They announced that they refused to do military service and that, in return, they had been involved in a social project for eight months to aid neighbours in the Can Serra neighbourhood, in L'Hospitalet de Llobregat. They offered literacy work, elderly care and a kindergarten service, among other activities.

The message spread across the country and with it began the largest civil disobedience movement in Europe. After the Can Serra message, objector groups began to flourish throughout Spain and would end up involving more than a million young people for almost 30 years. Many of them preferred to go to prison in exchange for making a claim visible - ending the military service - which spread like an oil stain at the dawn of the Transition.

"Can Serra was capital", recalls Pepe Beúnza, one of the young people who signed the manifesto and the first conscientious objector for political reasons in the country. Beúnza had already gone through several jails then for refusing to serve in the military, but his claim did not have enough impact. "Until that moment we had only taken individual actions and the manifesto changed everything: it turned our claim into something collective and unstoppable."

Beyond the pacifist and antimilitarist motives for opposing the military service, the experience represented, for many, a traumatic moment of youth. Abuses, humiliations and accidents were the routine in a barracks to which twenty-somethings arrived terrified from all corners of the country.

Military service was not just a bad experience: every year hundreds of recruits were killed and maimed in accidents. The injured numbered in the thousands and suicides were common to the point of becoming the leading cause of death. According to a 1985 survey, 20% of those who went to the military interrupted their studies, 15% lost their jobs and 13% their partner.

"Another thing that we managed to change was that conviction that existed in our society that one did not become a man until he passed through the military," adds Martí Olivella, another of Can Serra's objectors.

This is the story about how a Christmas message stirred the consciences of the youth of an entire country and projected a struggle, that of civil disobedience, from which all kinds of subsequent mobilizations have drawn: from anti-globalization activism to 15- M and even for the Catalan independence movement in October 2017.

The years of preparation

There is a French guy named André who to this day is not aware of the influence he has had on conscientious objection in Spain. André lived in an environmental commune in France and travelled to Valencia to learn how to grow rice in the mid-1960s. There, in a bar on Carrer de la Nau, he met a group of bearded university students who used to chat about politics. Among those who listened was Pepe Beúnza, a young student of Agricultural Engineering.

"It is incredible because to this day he does not know that he was the first to speak to us about conscientious objection for political reasons," recalls Beúnza. At that time, the only people who opposed the military were Jehovah's Witnesses, who entered jail because they refused to do military service for religious reasons.

André told them about a community in France called L'Arche, founded by the philosopher and disciple of Gandhi Lanza del Vasto. They were conscientious objectors, environmentalists, and pacifists. They did yoga and grew their own food. "He left us all impressed," says Beúnza. The following summer, 1967, he stands there with a friend and they tell him that in the Pyrenees there is another group of objector hippies doing rural development service as an alternative to military service. "It seemed formidable to me and that's where it all started."

Over the next four years, Beúnza will become Spain's first conscientious objector for political reasons. Before refusing to do the military service, he travels and seeks international support. He learns to do yoga and to play the flute assuming he will spend years behind bars. In January 71, he refused to wear the uniform and entered prison. Months later he is sentenced to 15 months in jail in a martial court. A march on foot from Geneva to Valencia gives an international echo to his case, but at that moment there are few young Spaniards willing to go through prison.

Until 1975 Beúnza will enter and leave the prison on several occasions. He is pardoned in November 71 and he again refuses to do military service. In December of that year he went to the Orriols neighbourhood, in Valencia, and started a civil service as an alternative to the military. He is arrested and returns to jail. He is sent to a disciplinary battalion in the Sahara. In March 1974 he was free again after three years and two months in which he had passed through two cells, ten prisons and the aforementioned battalion. At that time he still has to do the military service.

Beúnza spends the following year giving talks throughout the country explaining his case. More and more people are willing to follow his path. In April 1975 the first group of conscientious objectors was formed with the support of the activist Gonzalo Arias. That summer they retired for three days to the monastery of Montserrat, welcomed by the Benedictine monks, and they have just designed their plan. At that time there were five but many more will come.

The Can Serra neighbourhood

One member of the group, Martí Olivella, has lived for two years in a parish community in the Can Serra neighbourhood, in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat. There they have helped to create the neighbourhood association and the "house of reconciliation", a parish where activities of all kinds are carried out for the inhabitants of the neighbourhood.

"Can Serra had a very strong neighbourhood movement coordinated with the parish community," recalls Beúnza about that district in the process of reconversion, with more and more houses, fewer fields and still hardly any equipment. "There was a progressive part of the church, especially in Catalonia, whose role was very important for conscientious objection", adds Olivella.

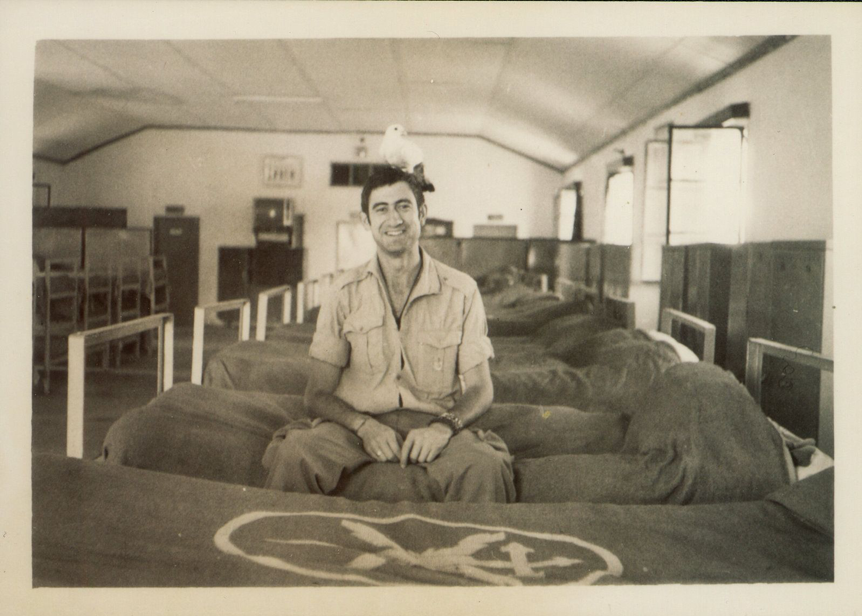

The objectors are going to live together in an apartment in that neighbourhood. They sleep on the floor with a mat and a sleeping bag. Some work to support the others, others are dedicated to preparing the action and looking for ways to finance themselves and all collaborate in the civil service that they have started in the neighbourhood.

They teach their grandparents to read (at that time in Spain there were seven million illiterates), they set up summer camps for the children who roam the streets of the neighbourhood, they held handicraft workshops, they fixed up a neighbourhood store, they started a day-care for the children of working women ...

Despite the fact that they are welcomed in Can Serra, both Beúnza and Olivella acknowledge that many of the neighbours saw them as strange creatures, at a time when much of the left-wing opposition still revered the armed struggle of armies such as the Cuban or South American revolutionaries. "We had the incomprehension of the right and the left," recalls Olivella. "Somehow we felt very alone."

At the same time, they are preparing the communication campaign. Thinking of the moment when they will be taken to jail, they record a short documentary together with a neighbourhood film cooperative and prepare a book of almost thirty pages in which they explain their case and the profiles of each one. When they have been in the neighbourhood for a few months, they set up a second floor where a second group of objectors will go to live, who will take over when the first team is imprisoned.

"Those months were extremely intense," says Beúnza, "the cohesion was very powerful, we were a group that was preparing for the sacrifice because we all knew that we would end up behind bars." Olivella remembers with nostalgia those months when a group of strangers who only had pacifism as a common denominator went to live together in a flat on the outskirts of Barcelona. "What Pepe says is true, it was very intense."

Christmas night 1975

Days before that night, Beúnza and Olivella tour the city on motorcycles, distributing the little booklet they have published to different churches thanks to the knowledge of Olivella, who works in a printing company. The booklet is carefully edited and describes the project, explains what conscientious objection is, summarizes the reasons for opposing military service, and includes a short biography of each of the objectors. The manifesto is titled 'A path to peace'.

Franco has been dead for barely a month and the international context is also favourable: the cold war, the hangover of May 68, the movement against the Vietnam War ... The world is changing, Spain even more so and the objectors know it. "We put together the right group at the right time," sums up Olivella.

The group of objectors spends that night at the mass of the Rooster in Can Serra, where the manifesto is read. The text will be read in different Catalan parishes that have progressive priests. The objectors do not know if they will be arrested that same night, although they will end up returning to their apartment without problems. It will take more than a month for the agents to break into their home at dawn and take them to jail.

"We were not afraid because we had been preparing the moment for a long time," says Beúnza. "You have fear when you hide from something, but we wanted them to stop us so that the claim would have more impact," adds Olivella, who was part of the relief group and did not sign the first manifesto.

Can Serra's objectors are arrested and thrown into jail after the manifesto, but the objective is accomplished. After that Christmas night, alternative civil service projects to the military arise in Malaga, Vic, Madrid, Bilbao ... The Transitional amnesty law will allow Can Serra's objectors to get out of jail, but military service will continue to exist and every time there will be more objectors.

The process will continue for decades. First they will be the objectors until in 1988 a substitute social service to the military is approved. The alternative, however, lasts twice as long as military service. The rebellious movement will then begin, which will bring with it a cultural explosion - publications, music groups - especially strong in Catalonia and the Basque Country. In the early 1990s, it is estimated that two-thirds of the inmates of the Pamplona prison were rebellious youth.

In 2001 compulsory military service was finally eliminated. "Not even in the most optimistic thoughts when I entered prison for the first time did I come to think that in 30 years we would end the military," Beúnza explains about the moment he received the news. It is estimated that from the time the Can Serra objectors published their manifesto until the military was eliminated, there were a million objectors, more than 50,000 rebels and a thousand young people who went through jail.

If you have liberated from the military service you should be grateful to these young people who one Christmas night 45 years ago began a path of no return.